Black History Month: Black Pioneers in the Automotive Industry

From the inventor of the modern traffic light to the first African American driver to win a NASCAR race, meet six Black trailblazers who left lasting legacies in the car world.

February is Black History Month—a great time to recognize the accomplishments of Black pioneers in the automobile industry.

From breaking down color barriers in NASCAR to patenting an essential safety mechanism, these six African American entrepreneurs, inventors and innovators have made significant contributions to the auto industry.

And while we cannot highlight every Black pioneer, we spotlight these six Black leaders who’ve impacted auto history and helped drive our industry and society forward.

Courtesy of The Historical Society of Greenfield, Ohio: www.greenfieldhistoricalsociety.org

Courtesy of The Historical Society of Greenfield, Ohio: www.greenfieldhistoricalsociety.org

Charles Richard Patterson

Charles Richard Patterson was born in Virginia, but moved with his family to settle in Greenfield, Ohio, as a child.

Patterson was a skilled blacksmith and inventor, and he was awarded patents for a thill coupling in 1887, a furniture caster in 1891 and a vehicle dash in 1905. In 1893, he bought out his business partner and formed C.R. Patterson & Sons Company, a successful horse-drawn carriage maker.

When Patterson passed away in 1910, his son Frederick steered the company toward competing with Henry Ford and producing “horseless carriages.” C.R. Patterson & Sons made two-door coupe Patterson-Greenfield automobiles from 1915 to 1918. After World War I, the company exited the car business to focus solely on producing buses.

In its heyday, C.R. Patterson & Sons was the country’s largest Black-owned manufacturer, with more than 70 employees. And while no Patterson-Greenfield automobiles or buses are known to exist today, the National Museum of African American History and Culture recognizes C.R. Patterson & Sons as our country’s only African American-owned and -operated automobile company.

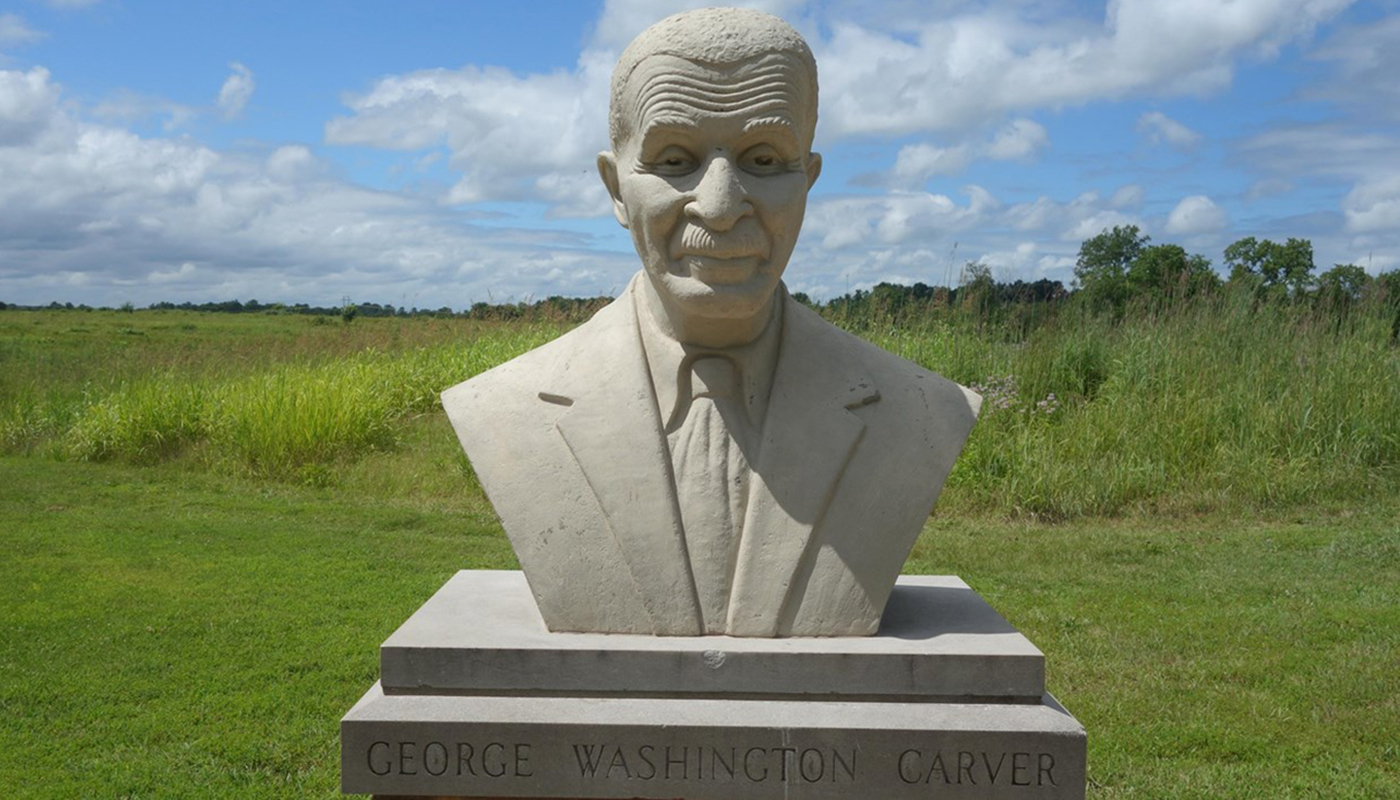

George Washington Carver National Monument and/or National Park Service

George Washington Carver National Monument and/or National Park Service

George Washington Carver

Born into slavery during the U.S. Civil War, George Washington Carver worked as a farmhand in Kansas to obtain a high school education. After a university in Kansas refused to admit him because of the color of his skin, Carver attended Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa, before transferring to Iowa Agricultural College in Ames, Iowa, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in agriculture in 1894 and a Master of Science in 1896.

Carver moved to Alabama in the fall of 1896 to head the department of agriculture at Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, a school led by famed African American educator Booker T. Washington. There, Carver would join Washington in his life-long mission of advocating that education could help African Americans get out of poverty.

While at Tuskegee, Carver conducted soil management and crop rotation experiments to help reestablish the South as an agricultural economic powerhouse. He found that farmers could plant peanuts and soybeans to restore nitrogen to the soil after it had been depleted by single-crop cultivation of cotton in much of the South.

To help farmers sell their new crops, Carver developed 300 products from peanuts, including milk, flour, plastics, linoleum, cosmetics and more. He also formed a friendship with automobile manufacturing magnate Henry Ford, and, to address the country’s shortage of rubber during World War II, made a synthetic rubber derived from the goldenrod plant.

Carver and Ford were both early adopters of biofuels, espousing the benefits of ethanol as a fuel alternative and sharing a vision of agricultural products being put to new uses for the betterment of society.

Learn more about African American history in your state.

Start ExploringRichard B. Spikes

Although little is known about Richard B. Spikes’ childhood and education, records indicate he was born in Texas in 1878. Well known are Spike’s many U.S. patents, including a beer tap (1907), an automatic gear shift (1932) and an automatic safety brake system (1962).

Spikes famously developed an automobile turn signal in 1912, which he installed in Pierce-Arrow cars in 1913. However, Spikes may not have been the original inventor of this device, as Percy Douglas-Hamilton was awarded a patent for a precursor to the modern automobile turn signal in 1909.

Still, Spikes’ engineering influence on the modern automobile can’t be understated. For his automatic transmission and gear shift innovations, Spikes received $100,000. His automatic safety brake system, patented in 1962, would soon become standard in almost every school bus in the country.

Spikes died in the 1960s, but he left behind an engineering legacy that few can match.

Wendell Scott

Wendell Scott was born in Danville, Virginia, in 1921. He learned about cars from his father, who was a mechanic. His first job was driving a taxi before he started running moonshine whiskey, which taught him to drive fast to evade police.

In 1952, Scott became the first African American to compete in an official stock car race. He’d go on to win several races in lower divisions while being denied entry into NASCAR because of his race.

Then, in 1961, Scott took over the racing license of NASCAR driver Mike Poston. He became the first Black driver in NASCAR’s top-tier circuit, and, in 1963, became the first African American driver to win a NASCAR premier series event at a 100-mile race at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Florida.

By the end of the 1973 season, Scott had accumulated 20 top-five finishes. He was inducted into the NASCAR Hall of Fame in 2015, with 495 career race starts to his name. It wasn’t until 2021 that another African American driver, Bubba Wallace, won a NASCAR race, almost a half-century after Scott accomplished the feat.

Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company

McKinley Thompson Jr.

Born in Queens, New York, in 1922, McKinley Thompson Jr. was keenly interest in cars from a young age.

After serving in the Army Signal Corps during World War II, he won a design contest hosted by Motor Trend magazine in the early 1950s, and the prize was a scholarship to the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California. He graduated from the college with a degree in industrial design.

In 1956, Thompson made history by becoming one of the first African American car designers in the industry when he accepted a designer position with the Ford Motor Company in Dearborn, Michigan. Among Thompson’s first projects was contributing sketches for the Ford Mustang. One of his most notable contribution, however, came in 1963 when he and other Ford designers created an open-air 4x4 concept that would become the iconic Ford Bronco.

Thompson retired from Ford in 1984 and passed away in 2006.

“McKinley was a man who followed his dreams and wound up making history,” said Ford Bronco interior designer Christopher Young in a February 2020 Ford Newsroom article. “He not only broke through the color barrier in the world of automotive design, he helped create some of the most iconic consumer products ever—from the Ford Mustang, Thunderbird and Bronco—designs that are not only timeless but have been studied by generations of designers.”

Garrett Morgan

Born in Paris, Kentucky, in 1877, entrepreneur and inventor Garrett Morgan began his career as a sewing-machine mechanic in Ohio. With just an elementary school education, he taught himself the inner workings of the machines, and then he obtained a patent for an improved sewing machine and opened his own repair business.

Following the success of his sewing machine business, Morgan founded G.A. Morgan Hair Refining Company after accidentally discovering a chemical solution that could also straighten hair. The serial innovator also patented a breathing device that became the prototype and precursor to the gas masks used to protect soldiers during World War I.

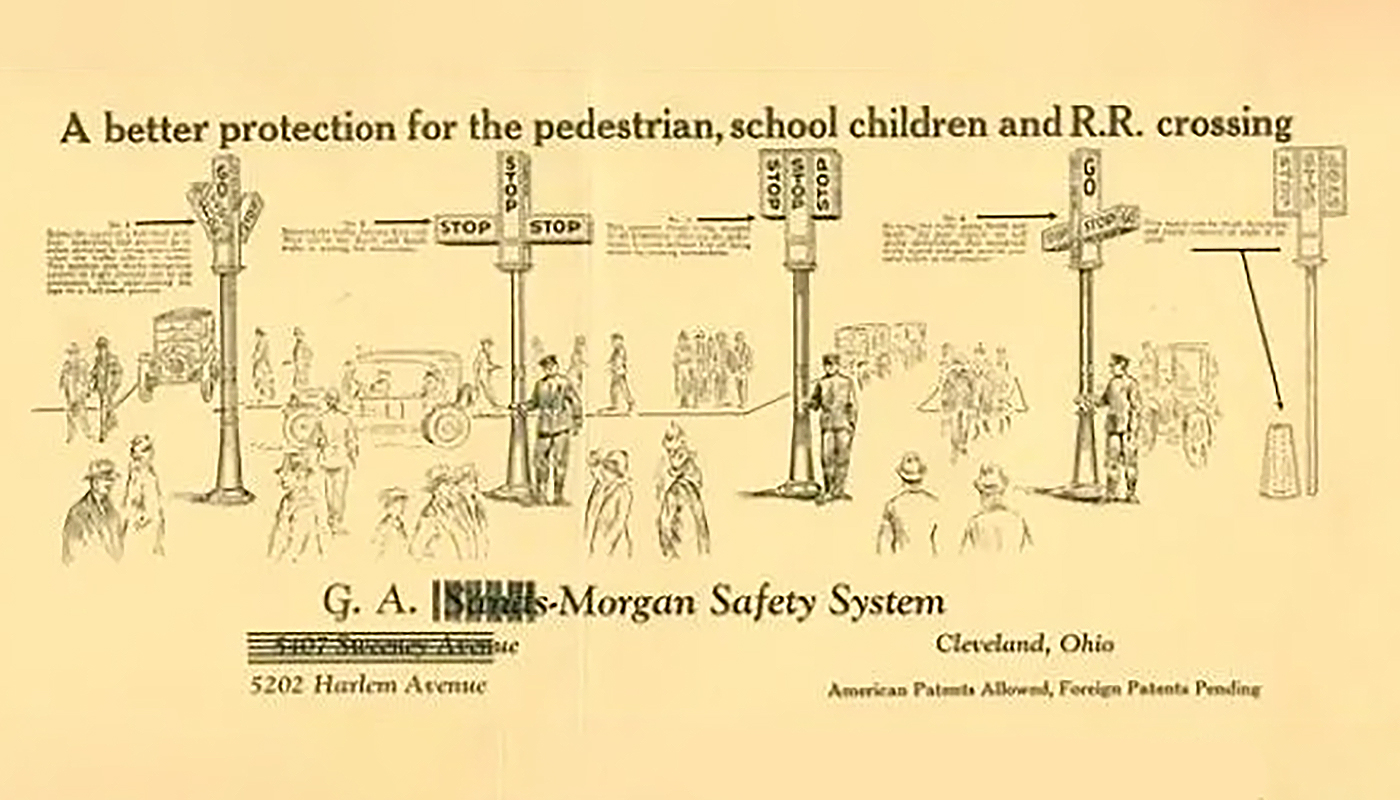

Courtesy of the Western Reserve Historical Society Archives

Courtesy of the Western Reserve Historical Society Archives

Morgan is perhaps most famous for inventing the first three-position traffic signal system in 1923 after witnessing a terrible horse-drawn carriage crash. He sold the idea to General Electric for $40,000. In essence, Morgan is responsible for adding the yellow light that has become standard on almost all modern traffic lights.

Celebrate Black History Month with AAA

Black History Month is an opportunity to celebrate the rich heritage and culture of the Black community, as well as reflect on the ongoing struggle for equality and justice. This month and all year, we affirm our continuing commitment to building an environment that reflects diversity and to promoting a culture that inspires all individuals to work together to achieve success.

To read more about our diversity, equity and inclusion vision and mission, click here.