Mystery of History: The Life (and Death) of Old West Legend John 'Doc' Holliday

.jpg)

Craig and Jessie Rosenberger visit the Doc Holliday memorial marker at Linwood Cemetery in Glenwood Springs. Holliday's actual resting place within the cemetery is unknown. © Pat Woodard

Standing at the trailhead to the historic Linwood Cemetery in Glenwood Springs, I felt a bit like one of the dusty, bedraggled, and frustrated posse members who tried and failed to bring Doc Holliday to justice after his latest outrage. There was the man he disfigured with a knife in Denver, another he shot in Trinidad. Gunnison, Silverton, and Pueblo all offered tantalizing tidbits about the gambler and gunslinger who always seemed to be on the run, whether from the law or from the tuberculosis that he knew might send him to his grave faster than either a bullet or the noose. The short walk ahead of me promises to finally provide something definitive to a search that has so far led me to more dead ends than the one just up the trail.

The story of John Henry Holliday, the “Deadly Dentist,” is familiar, at least as told by the Hollywood myth-making machine. My Darling Clementine (1946), Gunfight at the OK Corral (1957), Tombstone (1993), and many other movies and TV shows (even the original Star Trek) depict Doc Holliday’s unlikely alliance with lawman Wyatt Earp and his brothers. Some touch on Doc’s death in Colorado, but none talk about his life in the Centennial State, which included not only his early and violent forays into Colorado’s mining boom towns, but also the last four years of his life, which were not as uneventful as Doc himself would have liked. You can still find traces of that life today, if you look hard enough, and remember that chasing legends can be even more fun than catching facts.

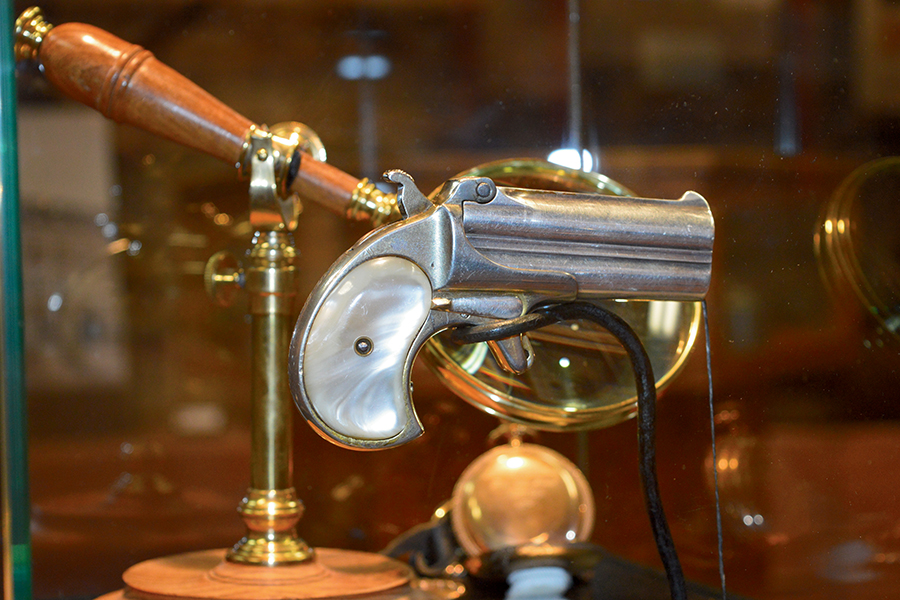

A reinforced display case equipped with alarm sensors protects a derringer reputed to have been in Doc Holliday's possession when he died. The Glenwood Springs Historical Society paid $80,000 to acquire the pistol. © Pat Woodard

Many of the structures Doc and his equally legendary cronies knew in Denver are long gone. The Windsor Hotel that once stood at 18th and Larimer in Denver is where, in 1882, Doc reputedly saw Wyatt Earp for the last time. After his lawman days ended, Bat Masterson dealt faro at 15th and Blake—where the Palace Variety Theater and Gambling Halls stood, not far from the jail where, years earlier, Doc awaited extradition to Arizona on a murder charge. Bat and Wyatt Earp cooked up a scheme to present a bogus robbery warrant against Holliday to the governor, who honored that instead of the Arizona murder extradition request, releasing Doc into Bat’s custody. I smile when I think of Doc, Bat, and Wyatt, though all the evidence I see of that era are some lofts that at least retain the “Palace” name.

I refined my search to undisputed Doc provenance in two Colorado towns—the one where he had his last gunfight, and the one where he died.

Doc Holliday lived most of his last four years, between 1883 and 1887, in the two-mile-high air of Leadville, an odd choice for a man with tuberculosis who needed all the oxygen he could get. I saw a boast on a travel website from someone claiming that they stayed in “Doc’s” room on the third floor of the Delaware Hotel. The Delaware is a grand old building, still receiving guests and putting on a Sunday tea. Doc gambled at establishments up and down Harrison Avenue (U.S. Route 24), but was most established at the Board of Trade Saloon, which still stands and is still a saloon, though it’s now called the Silver Dollar. Inside, the original bar and tile floors give some sense of what the place might have looked like in Doc’s day. Across Harrison Avenue from the Silver Dollar is another of Doc’s old haunts. The Hyman Block now consists of bike racing and curio shops adjacent to the Tabor Opera House, but it once housed the Monarch Saloon, where a fight over a $5 debt erupted in gunfire on Aug. 19, 1884. When the smoke cleared, Doc’s antagonist was bleeding from a bullet to the arm that severed an artery, and Doc was headed to the county jail, charged with attempted murder. He was acquitted on grounds of self-defense.

By the spring of 1887, the long winters and high altitude of Leadville had taken their toll on Holliday’s already emaciated body. He moved to Glenwood Springs, hoping that the hot springs there might provide some relief from the disease that was consuming him. I made my way to the northeast corner of 8th and Grand in Glenwood Springs and paused at the entrance to Bullock’s, a western apparel and furniture store. A small sign declares, “Doc Holliday died here Nov. 8, 1887.” Bullock’s sits on the site of Doc Holliday’s last home, the Hotel Glenwood, which burned to the ground long after Doc’s demise. In the store’s basement, I met Bill Kight, executive director of the Doc Holliday Museum, opened in August 2017.

“Doc Holliday is a mystery of history,” Kight says. “People are fascinated because of the potential, not just the reality of Doc’s story.”

That’s apparent by some of the movie posters and autographed photos provided by the likes of Doc’s portrayers, including the actor Val Kilmer, whose “I’m your huckleberry” line from 1993’s Tombstone is now so associated with Doc that it doesn’t seem to matter whether he actually ever said it.

Kight shows me an exposed beam that is all that remains of the Hotel Glenwood, where just before breathing his last, Doc is said to have uttered “This is funny”—his amusement springing from a glimpse of his bare feet and the realization that he would not die with his boots on during a gunfight. Kight seems skeptical of the story, noting that Holliday was in a coma the last days of his life.

One of Kight’s favorite artifacts on display is a medical instrument that came from Tombstone, Ariz.: a bullet puller used to extract slugs from the bodies of the dead and wounded after the shootout at the OK Corral.

In the middle of the museum sits a locked case of reinforced glass and plastic, hooked up to sensors that will trigger an alarm should someone try to disturb the contents. Inside the case, a magnifying glass hovers over a gold watch, providing a view of the inscription on the watch case: “John ‘Doc’ Holliday, From Your Friend Wyatt Earp, 1881.” Next to the watch sits the object that is to this museum what the Mona Lisa is to the Louvre.

A pocket watch on display at the Doc Holliday Museum in Glenwood Springs bears an inscription purported to be from one of Doc's few real friends: Wyatt Earp. © Pat Woodard

The Glenwood Springs Historical Society paid $80,000 to acquire the derringer in the fortified display case. An inscription on the handle reads that the gun was a gift to Doc from his common law wife, “Big Nose” Kate Elder. Reputedly, it was in Doc’s possession when he died, but Bill Kight concedes that the gun’s history remains unproven, which he figures just adds to the Doc Holliday legend.

Which brings me to my hike into Linwood Cemetery. I look forward to something that’s not shrouded in uncertainty and half-truth. The trail winds up a hillside with a commanding view of the region. It’s a pretty place to spend eternity. I quickly reach an obelisk with the inscription: “John Henry Holliday. Born Aug. 14, 1851. Died Nov. 8, 1887.” People leave items here in homage to Doc. I see a playing card held down by a rock. Then I spot something else inside the fence, a plaque bearing the words, “This memorial is dedicated to Doc Holliday who is buried someplace in this cemetery.” What? Someplace? It turns out that nobody really knows exactly where Doc is buried, the result of lost burial records and flash floods. There’s speculation that he’s in the cemetery’s “potter’s field,” reserved for the community’s destitute. Some of Doc’s devotees say he’s not buried here at all, that his family claimed his remains and transported them to his birthplace in Georgia.

Once again, I’m chasing a character who is every bit as slippery in death as he was in life. Would I do it again? I’m your huckleberry.

Pat Woodard is a freelance writer based in Parker, and frequent contributor to EnCompass. He’s a longtime Denver radio and television broadcaster, high-country hiker, avid fly fisher, and losing contestant on Jeopardy.